We’re nearing the time when we finally re-established contact with my father, after four years of captivity.

He had been imprisoned in the special prison, about 60 miles from Beijing, especially built to hold the top political prisoners. Its first inmates had been officials from the Guomintang – but now it held my father and all the other ministers denounced by the Cultural Revolution. It featured a maze of high walls that kept any prisoner from meeting another, and ironically enough – inspecting it had been one of my father’s duties when he worked for the Security Ministry. (As you might recall from an earlier episode, he took some of us kids for a holiday there to visit the scenic surrounding hills while he was working at the prison. On the way home, our driver baked delicious, sweet yams on the engine block of the automobile)

But now, of course, he was prisoner, not administrator, and that very same driver who had baked us the yams later accused him of taking advantage of his job to give his children leisure.

Every prisoner had his own cell – 6 feet on a side – just enough space for a bed, a toilet hole , and a sink – and each prisoner lived in total isolation beneath an electric light that burned 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Once a day, prisoners were carefully led to the prison yard– one at a time – in such a way that they would never meet each other. In the yard they stood for one hour in a cell just like the one they had left – except that it was empty and had no ceiling. It was their daily chance to see the sky.

Those early Guomintang prisoners had been given pen and paper, so that, in ancient Chinese imperial tradition, they could write the history of their previous regime. ( Dad had been one of the few party officials who could subscribe to their publication. Unfortunately, over the years, many have been lost. We still have 30 – 40 of what were once 80 – 100 volumes.)

But these new prisoners were given nothing: no pen, no paper, and only one book: Chairman Mao’s little Red Book – which my father memorized word-by-word, cover to cover.

The prisoners were sufficiently fed. Once a day, a tray of food was shoved beneath their door – and the higher ranking inmates were even given a cup of milk.

But this complete isolation had to be a real challenge to mental health.

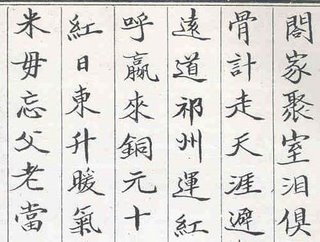

My father practiced a regimen of mental and physical exercise that included some Chi-gung and martial punching exercises that he had learned in his youth – and walked several kilometers every day through the 2 meters of his cell Lacking any sound to break the quiet, he made his own, by drumming on his sink with his chop sticks ---(a daily practice that he continued -much to our dismay - for several years after his release ) And lacking pen and paper, he memorized his own poetry as he wrote it. Over the course of those six years – he wrote 250 poems about his childhood – which he would eventually calligraph with brush on paper after he had been released. (a detail of which is shown at the top of this post)

The prisoners were not tortured or beaten (unless their shouts angered the guards) – but over the course of many years – complete isolation is torture enough.

After four years, our family was finally notified of his imprisonment – and just as I was returning to Beijing with my mother, we got to pay him his first visit.

All six of us gathered in Beijing and were loaded into a van that drove us out to the prison.

What a tearful reunion that was !

My father looked terrible – and we even had a hard time recognizing each other . His head was shaved, and he wore the prison uniform of black pants with a black cotton padded jacket. He had gained some weight, and his eyes were sunken in a face so pale and swollen.

I began sobbing – and could not stop until later that evening – after which came a very bad headache that lasted throughout the night. We had gotten very close during those six months we’d spent together after I transferred to the school near his work – and it hurt me so much to see him suffering like this.

And he had difficulty recognizing some of us – my younger sister and I – as the previous four years had changed our adolescent appearance as well.

We spent three hours together with him in a special visiting room – telling him our stories – and I suppose that I especially remember his reaction to mine: he wept to hear that I had been sent north to the Russian border – because he knew that this had been the destination of all kinds of criminals, and he feared for my safety.

The family would make many more such visits over the next two years – about one every 8 weeks -- but since I would soon be sent to another part of the country, I only saw him a few more times before he was eventually released.

And when would he be released ?

There had never been a trial – there had never been a sentence – there had only been an order for incarceration –and since Chou Enlai had signed that order, nobody wanted to countermand it. As it turned out – neither Chou nor anyone else would ever sign for his release – but two years later – after nearly 6 full years in solitary confinement – my father, and all the other prisoners of the Cultural Revolution – were set free.

There were quite a few stories like ours – like my father’s former boss who was arrested soon after he had remarried following the death of his first wife.

His new son never met his father until he was six years old.

Later, of course, the prison received a new generation of prisoners, including the Gang of Four in 1976, shortly after Mao’s death. One died of cancer - Madame Mao supposedly managed to kill herself while in hospital – and one of them, the young radical who had been chosen as Mao’s successor, went mad and was kept in prison until his death in 2005.

No comments:

Post a Comment